Bulletin – September 2020 Australian Economy The Rental Market and COVID-19

- Download 792KB

Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic is an unprecedented shock to the rental housing market, reducing demand for rental properties at the same time as supply has increased. Households most affected by the economic impact are more likely to be renters, and border closures have reduced international arrivals. The number of vacant rental properties has increased as new dwellings have been completed and some landlords have offered short-term rentals on the long-term market, particularly in inner Sydney and Melbourne. Government policies have supported renters and landlords. Rents have declined, partly because of discounts on existing rental agreements and it is likely that rent growth in many areas will remain subdued over coming years.

The COVID-19 pandemic is an unprecedented shock to the rental housing market

The pandemic-induced economic downturn has disproportionately affected households with the strongest ties to the rental housing market. Job losses have been much more pronounced for younger workers, who are more likely to rent homes. By industry, the effects of Australia's COVID-19 restrictions have been largest in the accommodation & food and arts industries, where employment is tilted towards younger workers, often living in the inner suburbs of Australia's major capitals.

One-third of Australian households rent, mostly in the private rental market (Graph 1). Renters tend to be younger than owners, with close to two-thirds of households headed by someone under the age of 35 renting. Renters also tend to have lower incomes and spend a larger share of their disposable income on housing costs compared with owner-occupied households (both outright owners and those with a mortgage).

In the wake of the pandemic, the rental market has experienced shocks to demand and supply. Weak labour market conditions, including the temporary closure of many service businesses, have reduced demand for rental properties as households have consolidated to save money and requested rent reductions or deferrals. The closure of international borders magnified the demand shock, as the flow of international students and other migrants (who typically rent) has slowed. On the supply side, with the number of international tourists and domestic travellers falling, a large number of short-term accommodation providers have shifted their properties onto the long-term rental market. The vacancy rate has increased sharply in some markets.

Prices in rental markets have adjusted in response to reduced demand and higher supply, which in turn has had implications for consumer price inflation.[1] Advertised rents declined sharply from April, particularly for apartments in Sydney and Melbourne. In addition, policy measures such as the moratorium on rental evictions have encouraged tenants and landlords to renegotiate the terms of their existing leases. In the June quarter, these factors drove the first quarterly fall in rents in the history of the Consumer Price Index (CPI). Over time, some of these trends in demand and supply are expected to evolve in a way that supports rents. For instance, the eventual reopening of the borders to international migration will lift demand for rental properties while reduced construction activity will translate into lower-than-otherwise growth in the supply of new dwellings.

Demand for rental properties has declined …

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in the largest economic shock since the 1930s, and households' exposure to – and ability to weather – this shock is uneven. Around one in five households only have enough liquid assets to get from one pay period to the next (RBA 2020). These liquidity-constrained households tend to be younger, more likely to work in industries such as accommodation & food services and arts & recreation where job losses were initially most pronounced, and also twice as likely to rent. In metropolitan areas, payroll job losses from March to July have been most pronounced in Melbourne and inner Sydney. In the near term, renters with limited savings and who are experiencing job insecurity are likely to reduce their spending on housing.

As a result of international border closures, net overseas migration is expected to slow considerably, further reducing demand for housing over the coming year. Treasury forecasts that Australia's population will be 1½ per cent lower by June 2021 compared with pre- COVID-19 projections, equivalent to around 400,000 fewer residents.[2] A decline in population growth of this magnitude would result in a decline in rents of around 3 per cent nationally over the next few years, compared to pre- COVID-19 expectations, based on a model that uses historical experience (Saunders and Tulip 2019). The number of international students in Australia has declined; around one in five student visa holders had not arrived in the country by late March. According to the 2016 Census, international students are more likely to rent and live in apartments, and twice as likely to live in inner-city areas than domestic students.

… and the supply of longer-term rental accommodation has increased

The supply of properties on the long-term rental market has increased as properties previously listed on the short-term market and newly completed dwellings have become available. The increase in supply has not been uniform by dwelling type or location. Although rental market apartments typically account for around 10 per cent or less of the total dwelling stock in each state, around half of all apartments are rented (Graph 2). As with the changes in demand, changes in supply have been pronounced in inner areas of Melbourne and Sydney. Since mid March, longer-term rental listings increased by much more in inner Sydney and Melbourne compared with the rest of the country (Owen 2020).[3]

Many landlords have taken down their short-term accommodation listings in response to the sharp fall in international visitors and domestic travellers. On Airbnb alone, listings declined by around 20 per cent, or 40,000 properties, between February and May (Graph 3). Around three-quarters of all Airbnb listings are entire homes or apartments, which owners could list on the longer-term rental market (Sigler and Panczak 2020). Assuming entire dwellings make up a similar share of delisted properties and all these were converted to longer-term rental accommodation, the national vacancy rate would initially increase by around 1 percentage point.[4] Short-term accommodation also tends to be more concentrated in the inner suburbs of Sydney and Melbourne and around 40 per cent are apartments.[5] Looking ahead, if domestic virus containment measures are successful, some properties may transition back to the short-term market to take advantage of the recovery in domestic tourism and business travel.

Longer-term rental supply will also be boosted by apartments that are due to be completed over the next year or two. A large share of these are high-rise apartments that commenced construction a number of years ago when conditions in the established housing market were much stronger (Rosewall and Shoory 2017). In Sydney and Melbourne, the number of apartments estimated to be completed over the next two years is equivalent to around 4 per cent of the non-detached dwelling stock (Graph 4). In Melbourne, over half of the pipeline of apartments yet to be completed is located in the city and inner suburbs, compared to around one-quarter in Sydney.

It takes time for supply to adjust in response to weaker demand from lower population growth. While contacts in the Bank's liaison program have reported that low rents and higher rental vacancy rates are already contributing to weak investor demand for off-the-plan apartments in Melbourne and Sydney, these projects are yet to enter the pipeline of construction activity. Over the medium term, the pipeline of apartments due to be completed, combined with weaker population growth, is expected to see the national vacancy rate increase by around 1 percentage point by 2021 before declining slowly as supply adjusts and international borders reopen.[6]

Government policies have helped support rental market conditions

At the National Cabinet in late March, state and territory governments agreed to a set of guiding principles for temporary changes to legislation governing the rental housing market in response to COVID-19. Most jurisdictions implemented an initial 60-day moratorium (which expired in mid June) on evicting tenants and used this time to develop a more comprehensive policy package that supported both tenants and landlords, including restricting evictions for tenants impacted by the pandemic until at least 30 September.

Each state and territory implemented their own policy package for the rental housing market. Most governments introduced regulations limiting the ability of landlords to evict tenants who had suffered financial hardship as a result of the pandemic. In most states, landlords and tenants were required to negotiate in ‘good faith’ a rent reduction or deferral before administrative tribunals would consider an eviction application. In return, landlords received land tax relief and deferrals commensurate to the size of the rent reduction they granted to their tenants. Some states offered cash payments to tenants in financial distress due to the pandemic South Australia and Victoria have extended these provisions until the end of March 2021 as economic conditions remained soft (for further details of the rental market measures by jurisdiction, see Table A1).

These policy measures combined with the provision of income support measures, including the JobKeeper program and the Coronavirus Supplement, helped offset the acute fall in rental demand and stabilise the rental market. Housing search interest fell sharply in late March (Graph 5). From April, these policy measures combined with a decrease in advertised rents have seen search volumes rebound. Bond lodgements have also increased, particularly in Sydney's inner and middle suburbs. This suggests that a tenant-favourable market is enabling renters with the capacity to do so to move into properties with lower rents or better amenities.

Rent payment relief on existing leases has been an important way the rental market has adjusted. Since the end of March, close to 15 per cent of tenants with existing residential leases have received some relief on their leases, according to data from property management platform MRI (Graph 6).[7] Rent relief has been split evenly between discounts and payment deferrals. Discounts reduce the rent owed by the tenant, whereas deferred rent is expected to be repaid eventually – lowering the rent paid temporarily, but not the rent owed. Evidence from surveys report a fairly wide range of estimates for the number of renters who have received some form of rent relief. The cumulative effect estimated from the MRI data is broadly consistent with the estimate suggested by the Australian Bureau of Statistics Household Impacts of COVID-19 Survey conducted in mid May but lower than surveys conducted by the Australian National University and Better Renting (at the same point in time; see Biddle et al 2020 and Dignam 2020).

Discounting and deferral activity increased sharply in the last week of March – coinciding with the announcement of the six-month moratorium on evictions – and peaked in April. While the rate of new discounts and deferrals has slowed since May, both remain higher than at the same time last year. By state, the increase in discounting was most pronounced in New South Wales and remained elevated in recent months (Graph 7). In Victoria, the discounting rate peaked at a lower level in May and increased again following the reinstatement of restrictions. In most other states and territories, discounting rates have returned to around their early-March levels.

Vacancy rates have increased sharply and rents have fallen in inner Sydney and Melbourne

Rental vacancy rates have increased, particularly in areas where the pandemic has had the strongest impacts on rental demand and supply. While policy interventions have helped prevent much larger rental market dislocations, the increases in vacancies in Sydney and Melbourne since March have still been pronounced (Graph 8). Vacancy rates increased by around 2 percentage points in the inner regions of Sydney and Melbourne and a little more than 1 percentage point in the outer suburbs of Sydney, but were broadly unchanged in regional Victoria. In Brisbane, vacancy rate increases were also most pronounced in the inner suburbs, where vacancies increased by a little over 1 percentage point in the June quarter (REIQ 2020). In contrast, Perth vacancy rates declined to 1.6 per cent in the June quarter, reflecting limited new supply following the post-mining boom downturn in dwelling construction in Perth and strong demand (REIWA 2020). Vacancy rates increased in Canberra in the June quarter, but declined in Hobart.

This increase in the vacancy rate is putting downward pressure on advertised rents as landlords compete for tenants. Advertised rents for apartments have fallen by much more than for houses, with the declines particularly pronounced for units in Sydney and Melbourne (Graph 9). The concentration of the shock in these markets is reflected in the largest divergence in housing and apartment rental growth since the start of the advertised rents series in 2005. By contrast, advertised rents for houses in Perth have increased strongly in recent months, although this follows several years of weak growth.

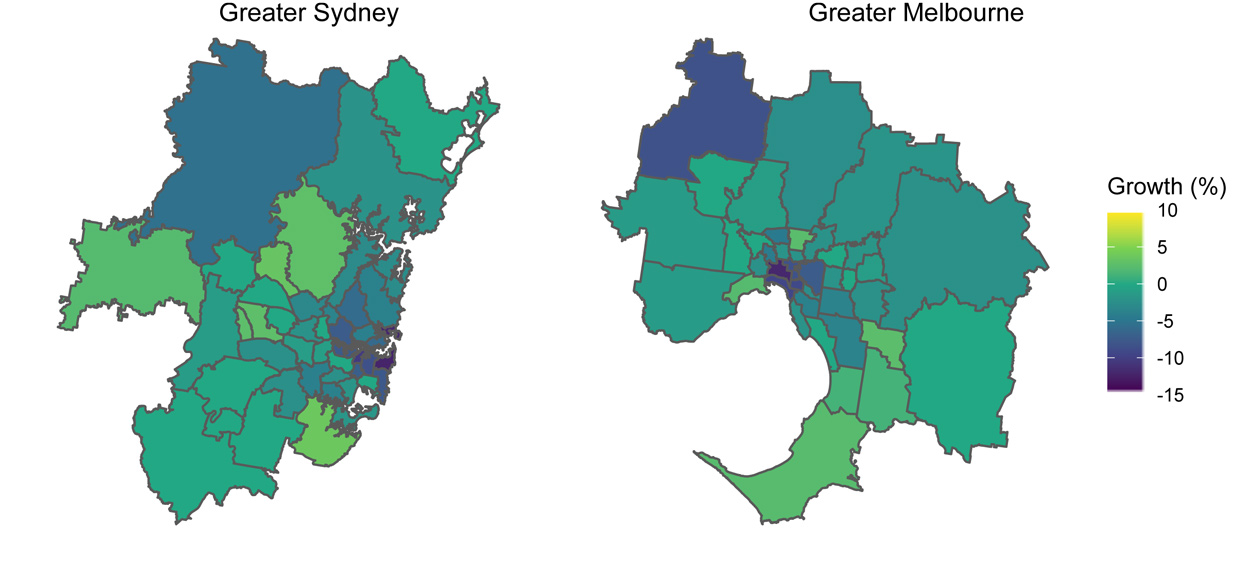

The falls in advertised rents have also been largest in the inner areas of Sydney and Melbourne (Figure 1). These areas were more adversely affected by declining demand from fewer international students and the conversion of short-term accommodation to the long-term rental market. These were also areas where employment was disproportionately affected by lockdowns. In Sydney, the largest declines in median advertised rents were recorded in the Eastern Suburbs, Manly and Leichhardt areas, where rents declined by over 10 per cent in the June quarter while in the Melbourne CBD, rents declined by 13 per cent. These were the only capital city areas that recorded double digit declines in the June quarter.

- View interactive map 11MB

- Map data 16KB

Rental income for landlords has fallen as a result of the decline in rents and increase in vacancy rates. Many of these investors are lower-to-middle-income earners, and for some of these households a shock to their rental income would significantly impact their livelihood (RBA 2017). Around 60 per cent of investors with rental properties operated at a net rent loss in 2017/18 (ATO 2020). Some of these landlords may have trouble making debt payments, though mortgage payment deferment by lenders has mitigated these risks for now. Working in the other direction, investors with the highest level of debt relative to their income tend to have higher income and/or wealth and so may be better positioned to absorb income falls. In addition, the share of investors with large portfolios of rental properties is small; only 4 per cent of investors have interests in four or more investment properties. Since the onset of the pandemic, around one in ten investors have applied for mortgage payment deferrals, which is a little less than the share of owner occupiers who have applied for mortgage relief. This suggests that from a serviceability perspective, most investors do not appear to be stretched.

Weaker rental market conditions are weighing on inflation. In the CPI, rent inflation measures the rent paid on the stock of existing rental properties. This means that changes in advertised rents, which only capture changes in the rents paid for the flow of new tenants, flow through to CPI rents with a lag. However, the rental relief provided by landlords on existing leases is reducing some tenants' rental burden; discounting reduced rent obligations in the June quarter by 0.5 per cent. In addition, because of the increase in renters entering into new leases, declines in advertised rents have been realised by more tenants. These two factors contributed to CPI rents falling by 1.3 per cent in the June quarter; the first ever decline in the 48 years for which quarterly data are available (Graph 10). The declines were largest in Sydney and Melbourne, the cities that have been most affected by COVID-19 containment measures.

Implications and outlook

The COVID-19 pandemic is a unique shock to the rental market. The economic consequences have disproportionately affected the households most likely to rent – young, inner-suburban workers, international students and new migrants. The ban on international tourism and significantly reduced domestic travel has increased supply as short-term rentals are offered on the long-term rental market.

In response, prices have adjusted in the rental market at the fastest pace in several decades. This has reflected both sharp declines in advertised rents for new leases and also rent relief on existing leases, encouraged by government policies to limit evictions and promote rent negotiations for affected tenants. The available evidence suggests these measures have been effective: rent discounts and deferrals rose sharply and remain above pre- COVID-19 levels in most states; and search interest for rental properties and bond lodgements in Sydney are high, suggesting renters who are able to do so are moving to realise lower rents. Income support measures have also smoothed the shock by reducing the magnitude of price adjustment needed, and likely reduced the number of tenants breaking leases.

In the near term, the successful suppression of COVID-19 and the controlled reopening of international borders in 2021 would result in increased rental demand in inner Sydney and Melbourne, reducing vacancy rates and supporting rents. Alternatively, setbacks in controlling the virus in Australia and internationally may delay the reopening of international borders, prolonging the loss of demand from international tourists and students. Domestic demand for inner-city rentals is also likely to remain lower in this scenario. Rent growth will likely remain subdued as a result. Over the next few years, it is likely that rents in these inner-city areas will remain lower than expected pre-pandemic given lower population growth and the anticipated supply of apartments coming on line in these markets.

Appendix A

| State | Policies |

|---|---|

| New South Wales |

$440m in land tax relief of up to 25 per cent of land tax due between 1 April

and 30 September if the savings were passed on to tenants. Outstanding

land tax could also be deferred for three months.

Evictions for rent arrears restricted until 15 October for COVID-19 impacted tenants. Impacted tenants could not be evicted for rent arrears unless an application was made to the NSW Civil and Administrative Tribunal and the landlord could demonstrate they engaged in good faith negotiations over rental payments, and it would be fair and reasonable to evict the tenant. Blacklisting tenants in rent arrears due to COVID-19 was also banned during this period. |

| Victoria |

$500m in land tax relief of up to 50 per cent (increased from 25 per cent

in August 2020) of land tax due for commercial and residential tenancies,

if rent relief was provided to tenants. Remaining land tax payable can

be deferred to March 2021.

Evictions were banned for residential tenancies (except in limited circumstances) from 29 March 2020 to 28 March 2021, after being extended from an initial six month period during the second lockdown, and rent increases paused for the same period. Tenants unable to secure a rent reduction could enter a binding dispute resolution process overseen by Consumer Affairs Victoria. Blacklisting tenants in rent arrears due to COVID-19 was also banned during this period. Both residential and commercial tenants could apply for grants of up to $3,000 from the Rental Relief Grant Program. To be eligible, renters needed to have registered their revised agreement or gone through mediation, have less than $5,000 in savings and still be paying at least 30 per cent of their income in rent. |

| Queensland |

$400m in land tax relief up to 30 October for residential tenancies if equivalent

rent relief was provided. Land tax could also be deferred for three months.

Payments of up to four weeks rent or $2,000 to those affected by COVID-19 who had no access to other financial assistance, and met asset tests. Tenants who were significantly impacted due to COVID-19 could not be evicted or blacklisted until 30 September. Fixed-term leases expiring before this date were automatically extended to 30 September. |

| South Australia |

$189m in land tax relief of up to 50 per cent of land tax due for commercial

and residential tenancies, if rent relief was provided to tenants. Remaining

land tax payable could also be deferred for six months.

From 30 March 2020 to 31 March 2021, landlords could not evict or blacklist tenants for non-payment of rent due to loss of income resulting from COVID-19. Rent increases were also banned during this period. $1,000 grants were paid to landlords who provided rent relief to their tenants until 30 September. |

| Western Australia |

$100m for 25 per cent reductions in land tax for commercial landlords who

provided at least three months' rent relief to tenants suffering

financial hardship due to

COVID-19.

From 30 March to 30 September, landlords could not evict or blacklist tenants for non-payment of rent due to loss of income resulting from COVID-19. Rent increases were also banned during this period. $30m in $2,000 grants for residential tenants who faced financial hardship due to COVID-19. |

| Tasmania |

From 30 March to 30 September, landlords could not evict or blacklist tenants

for non-payment of rent due to loss of income resulting from

COVID-19. Rent increases were also banned during this period.

Rent support payments for tenants of up to four weeks or $2,000 were available from 25 May to 30 September. |

| Australian Capital Territory |

Land tax and rate relief of 50 per cent of the rent reduction to a maximum

of $100 per week from 1 April to 1 October, if rent reduced

by at least 25 per cent for this period.

From 22 April to 22 October, landlords could not evict or blacklist tenants for non-payment of rent due to loss of income resulting from COVID-19. Rent increases were also banned during this period. |

| Northern Territory | Extension on period for rent negotiation from 14 days to 60 days. Notice period for lease terminations were extended to 60 days. Unlike other states and territories, the NT did not implement a moratorium on evictions. |

|

Sources: State and territory governments; RBA |

|

Footnotes

The authors are from Economic Analysis Department and would like to thank Cameron Deans, Emma Greenland and Andrew Staib for their contributions to this article. [*]

Rents make up around 7 per cent of the Consumer Price Index basket, meaning developments in rent inflation are an important driver of overall inflation. [1]

This is based on the updated population growth assumptions in the July 2020 Fiscal and Economic Outlook, which are 0.5 percentage points lower in 2019/20 and 1.1 percentage points lower in 2020/21 than the previous Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook in December 2019 (Australian Government 2019; 2020). [2]

The top six areas that recorded the largest percentage increase in listings from the four weeks to 15 March to the four weeks to 9 August were all located in inner Melbourne and Sydney. [3]

This is an upper bound estimate of the initial (partial) effect. Over time vacancies would decline as rents adjust. [4]

Three of the top six statistical area 2s (SA2s) by number of Airbnb listings are located in inner Sydney or Melbourne (Sigler and Panczak 2020). [5]

According to results from the Saunders & Tulip (2019) housing model. [6]

This platform covers around one fifth of all residential tenancy agreements in Australia. The rent relief estimate is an upper bound, and may double count leases that have had rent deferred or discounted more than once in the past four months. [7]

References

Australian Government (2019), ‘Part 2: Economic outlook’ Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook, December, viewed 8 September 2020. Available at <https://budget.gov.au/2019-20/content/myefo/download/02_Part_2.pdf>.

Australian Government (2020), ‘Part 2: Economic outlook’ Economic and Fiscal Update, July, viewed 8 September 2020. Available at <https://budget.gov.au/2020-efu/downloads/02_Part_2_Economic_outlook.pdf>.

ATO (Australian Taxation Office) (2020), ‘Taxation statistics 2017-18: Individuals’, 17 July, viewed 8 September 2020. Available at <https://www.ato.gov.au/About-ATO/Research-and-statistics/In-detail/Taxation-statistics/Taxation-statistics-2017-18/?anchor=Individuals#Individuals>.

Biddle N, B Edwards, M Gray and K Sollis (2020), ‘ COVID-19 and mortgage and rental payments: May 2020’, ANU Centre for Social Research and Methods, Canberra, June, viewed 8 September 2020. Available at <https://csrm.cass.anu.edu.au/sites/default/files/docs/2020/6/ COVID-19_and_housing_FINAL.pdf>.

Dignam J (2020), ‘Rent due: renting and stress during COVID-19’, Better Renting, Canberra, August, viewed 8 September 2020. Available at <www.betterrenting.org.au/coronavirus_survey_report>.

Owen E (2020), ‘Corelogic Rent Listings Continue To Show Pain Points Around Inner City Markets’, CoreLogic site, 13 August, viewed 8 September 2020. Available at <https://www.corelogic.com.au/news/corelogic-rent-listings-continue-show-pain-points-around-inner-city-markets>.

REIQ (Real Estate Institute of Queensland) (2020), ‘Brisbane CBD Vacancy Rtes Spike After COVID-19’, 10 August, viewed 8 September 2020. Available at <https://www.reiq.com/articles/brisbane-cbd-vacancy-rates-jun/>.

REIWA (Real Estate Institute of Western Australia) (2020), ‘Perth's vacancy rate drops to a 12-year low’, reiwa.com.au site, 19 August, viewed 8 September 2020. Available at <https://reiwa.com.au/about-us/news/perth-s-vacancy-rate-drops-to-a-12-year-low/>.

RBA (Reserve Bank of Australia) (2017), ‘Box B - Households’ Investment Property Exposures: Insights from Tax Data ', Financial Stability Review, October.

RBA (2020), ‘2. Household and Business Finances in Australia’, Financial Stability Review, April.

Rosewall T and M Shoory (2017), ‘Houses and Apartments’, RBA RBA Bulletin, June, pp 1–12.

Saunders T and P Tulip (2019), ‘A Model of the Australian Housing Market’, RBA Research Discussion Paper No 2019-01.

Sigler T and R Panczak (2020), ‘Ever wondered how many Airbnbs Australia has and where they all are? We have the answers’, The Conversation, 2020/02/13.