Digital Currencies

Download the complete Explainer 205KBWhat are Cryptocurrencies?

Cryptocurrencies are digital tokens. They are a type of digital currency that allows people to make payments directly to each other through an online system. Cryptocurrencies have no legislated or intrinsic value; they are simply worth what people are willing to pay for them in the market. This is in contrast to national currencies, which get part of their value from being legislated as legal tender. There are a number of cryptocurrencies – the most well-known of these are Bitcoin and Ether.

Activity in cryptocurrency markets has increased significantly. The fascination with these currencies appears to have been more speculative (buying cryptocurrencies to make a profit) than related to their use as a new and unique system for making payments. Related to this, there has also been a high degree of volatility in the prices of many cryptocurrencies. For example, the price of Bitcoin increased from about US$30,000 in mid 2021 to almost US$70,000 toward the end of 2021 before falling to around US$35,000 in early 2022. Rival cryptocurrencies like Ether have experienced similar volatility. The extraordinary interest in cryptocurrencies has also seen a growing amount of computing power used to solve the complex codes that many of these systems use to help protect them from being corrupted. Despite the increased level of interest in cryptocurrencies, there is scepticism about whether they could ever replace more traditional payment methods or national currencies.

How Does a Cryptocurrency Transaction Work?

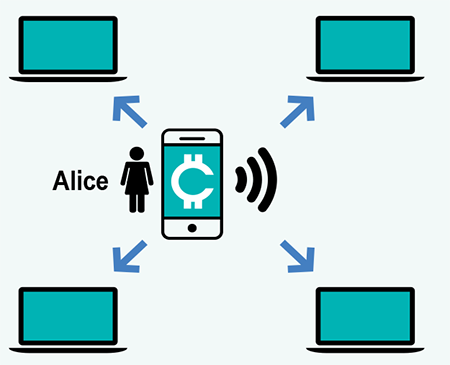

Cryptocurrency transactions occur through electronic messages that are sent to the entire network with instructions about the transaction. The instructions include information such as the electronic addresses of the parties involved, the quantity of currency to be traded, and a time stamp.

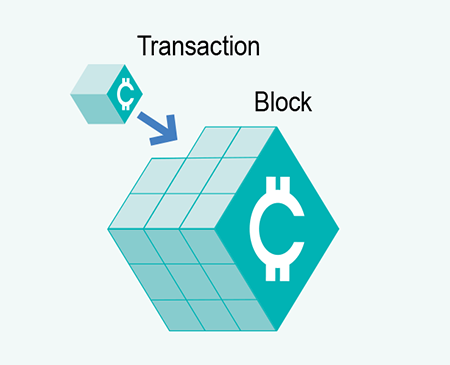

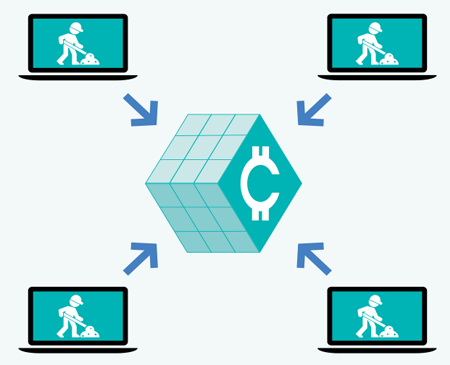

Suppose Alice wants to transfer one unit of cryptocurrency to Bob. Alice starts the transaction by sending an electronic message with her instructions to the network, where all users can see the message. Alice's transaction is one of a number of transactions that have recently been sent. Since the system is not instantaneous, the transaction sits with a group of other recent transactions waiting to be compiled into a block (which is just a group of the most recent transactions). The information from the block is turned into a cryptographic code and miners compete to solve the code to add the new block of transactions to the blockchain.

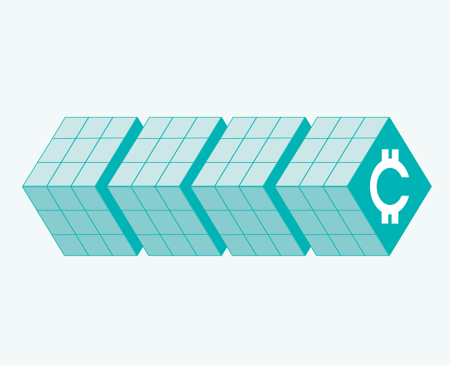

Once a miner successfully solves the code, other users of the network check the solution and reach an agreement that it is valid. The new block of transactions is added to the end of the blockchain, and Alice's transaction is confirmed. (This confirmation is not instant as it takes time for six blocks of transactions to be processed so that users can be certain that their transaction has been successful.)

Alice sends instructions to transfer cryptocurrency to Bob. Anyone using the network can view the message.

Miners group the transaction together into a 'block' with other recently sent transactions.

Information from the new block is transformed into a cryptographic code.

Miners compete to find the code that will add the new block to the blockchain.

Once the code is solved, the block is added to the blockchain and the transaction is confirmed.

Bob receives the cryptocurrency.

Is Cryptocurrency Money?

A frequently asked question is whether cryptocurrency can be defined as ‘money’. The short answer is that cryptocurrency is not a form of money. To understand why, we can ask whether the characteristics of cryptocurrencies match the key characteristics of money:

- Widely accepted means of payment – can cryptocurrencies be used to buy and sell things? Money generally comes in the form of a nation's currency, and is widely accepted as a means of payment. While cryptocurrencies can be used to buy and sell things, they are not widely accepted as a means of payment, and surveys suggest that only a small fraction of cryptocurrency holders use them regularly for payments.

- Store of value – can the purchasing power of cryptocurrencies (their ability to purchase a similar basket of goods and services) be maintained over time? Large fluctuations in the price of many cryptocurrencies mean that their purchasing power is not maintained over time, reducing their effectiveness as a store of value.

- Unit of account – are cryptocurrencies a common way of measuring the value of goods and services? In Australia, the prices of goods and services are measured in Australian dollars. While some businesses may accept cryptocurrencies as payment, they are not commonly used to measure and compare prices.

So, while cryptocurrencies can be used to make payments, currently their use as a means of payment is limited and they do not display the key characteristics of money.

However, there is one type of digital currency that could be considered money – digital currency issued by a central bank.

What is Central Bank Digital Currency?

A Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC) can most easily be understood as a digital form of cash. It can be issued by the central bank, accessible to the general public, and used to settle transactions between firms and households. The unit of account would be the national currency, and it could be exchanged at parity (i.e. one for one) with other forms of money, such as physical currency or electronic deposits with well-regulated financial institutions.

What are the main differences between cryptocurrencies and CBDCs? In other words, what makes a CBDC money? A central bank has the ability to ensure that a digital currency it issues exhibits the three main features of money – that is, a CBDC could function as a widely accepted means of payment, store of value and unit of account.

Because it is issued by a central bank, a CBDC would have legal tender status, making it widely accepted as a means of payment. A CBDC would also be an equivalent store of value to other forms of money, since it could be exchanged for an equal value of physical cash or electronic deposits. Finally, the unit of account for CBDC issued by the Reserve Bank would be the Australian dollar. This means it could be used to measure the value of goods and service. These and other key features have been summarised in the table below.

| CHARACTERISTIC | CRYPTOCURRENCIES | CBDCs |

|---|---|---|

| Means of payment | Accepted by a small number of retailers | Universally accepted, legal tender |

| Store of value | Tend to be volatile, depends on market price | Stable, consistent with central bank price stability mandate |

| Unit of account | Own unit of account | Fiat currency (e.g. Australian dollars) |

| Governance | Typically decentralised, relies on consensus between large number of entities. | Centralised |

| Transaction verification | Typically a large number of competing entities | Small number of trusted entities |

Surveys conducted by the Bank for International Settlements indicate that CBDCs are an active area of research for nearly all central banks. Despite this, only a few central banks have actually issued digital currencies – to date no high income country has issued a CBDC. The Reserve Bank remains cautious about whether issuing a CBDC would be in the public interest. Primarily, this is because many of the benefits of CBDCs have largely already been realised by existing technologies. In a 2021 speech, the Head of Payment’s said:

Reserve Bank staff have not been convinced to date that a strong policy case has emerged in Australia for a CBDC. The primary reason has been that Australia’s existing electronic payments system already provides households and businesses with a wide range of safe, convenient and low cost payment services.

What Are Some of the Public Policy Implications?

Some of the technology behind cryptocurrencies raises a number of considerations for public policymakers. Given the anonymity provided by cryptocurrency systems, and their worldwide reach, there are questions about how to limit the use of digital currencies for criminal activities. In addition, the current fascination with cryptocurrencies has potentially added to the speculative nature of these markets, and has raised concerns around consumer protection. If cryptocurrencies were to be more widely adopted, they could also present some challenges for the role of the banking sector and raise additional financial stability concerns in a crisis. Furthermore, the vast amounts of electricity used in the mining of cryptocurrency raise concerns about the allocation of resources and environmental consequences of these payment systems.

For more information about the risks involved with cryptocurrencies, see ASIC’s MoneySmart website.

In contrast, a CBDC could potentially support a number of public policy objectives, including safeguarding public trust in money and promoting efficiency, safety, resilience and innovation in the payment system. The Reserve Bank is continuing to closely examine the case for a CBDC and working with other central banks on this issue. The Reserve Bank is considering the relevant technical issues, as well as the broader policy implications.

While the Reserve Bank has not yet made a decision on whether to issue a CBDC, the Governor noted in his 2021 speech ‘Payments: The Future?’ that:

… the RBA is open to this possibility. To date, though, we have not seen a strong public policy case to move in this direction, especially given Australia's efficient, fast and convenient electronic payments system. It is possible, however, that the public policy case could emerge quite quickly as technology evolves and consumer preferences change. It is also possible that these tokens could offer a lower-cost solution for some types of payments than provided by the existing technologies.

For more information on the Reserve Bank’s research, see: Central Bank Digital Currency.

Features of the Bitcoin System

The most well known cryptocurrency is Bitcoin. Bitcoin was launched in 2009, a year after a report that described the Bitcoin system was released under the name Satoshi Nakamoto. The system was designed to electronically mimic features of a cash transaction. It was designed to allow peer-to-peer (or person-to-person) transactions, without the need to know or trust the other person in the transaction, and to occur without the need for a central party (such as a bank). Unlike conventional national currencies such as Australian dollars, which get part of their value from being legislated as legal tender, Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies do not have any legislated or intrinsic value. Instead, the value of Bitcoin is determined by what people are willing to pay for it in the market (and, in theory, its value could fall to zero at any time).

One feature of the Bitcoin system is that the supply of Bitcoins increases at a pre-determined rate and is capped at around 21 million (with each bitcoin able to be subdivided into 100 million satoshis or 0.00000001 bitcoins). Because of this, the supply of Bitcoins has been commonly compared to the supply of a scarce commodity, such as gold.

The Bitcoin system allows transactions to occur directly from person to person without requiring a central party (such as a bank) to verify or record the transactions. This is unlike most conventional payment methods, such as electronic bank transfers, which rely on a central party to keep and update records of transactions. For example, commercial banks maintain a record of their customers' account balances, deposits and withdrawals.

Instead, the Bitcoin system uses ‘blockchain’ technology to record transactions and the ownership of bitcoins. This is essentially technology that connects groups of transactions (‘blocks’) together over time (in a ‘chain’). Each time a transaction occurs, it forms part of a new block that is added to the chain. As a result, the blockchain provides a record (or database) of every bitcoin transaction that has ever occurred, and it is available for anyone to access and update on a public network (this is often referred to as a ‘distributed ledger’). The integrity of the Bitcoin system is protected by ‘cryptography’, which is a method of verifying and securing data using complex mathematical algorithms (or codes). This makes the system very difficult to corrupt.

Bitcoin transactions are verified by other users of the network, and the process of compiling, verifying and confirming transactions is often referred to as ‘mining’. In particular, complex codes need to be solved to confirm transactions and make sure the system is not corrupted. The Bitcoin system increases the complexity of these codes as more computing power is used to solve them. A new block of transactions is compiled approximately every ten minutes. ‘Miners’ want to solve the codes and process transactions because they are rewarded with new bitcoins (currently 6.25 new Bitcoins per block).

The increase in competition between miners for new Bitcoins has seen large increases in the amount of computing power and electricity required (which is often used for air conditioning to cool computer systems). While it is difficult to calculate with precision, some estimates suggest that the annual energy consumption of the Bitcoin system is roughly equal to the country of Thailand.

This explainer is provided to facilitate the conceptual understanding of cryptocurrencies. It does not constitute advice, or a recommendation, to buy, trade or invest in Bitcoin or any other cryptocurrency. If you decide to trade or use cryptocurrencies you may be taking on risk for which there is no recourse.

For more information about these risks see ASIC’s MoneySmart website.

References

Lowe, Philip (2021), ‘Payments: The Future?’, Address to the 2021 Australian Payments Network Summit, 9 December 2021.

Richards, Tony (2021), ‘Future of Payments: Cryptocurrencies, Stablecoins or Central Bank Digital Currencies?’, Address to the Australian Corporate Treasury Association, 18 November.